Untitled, watercolor sketch, 2024, Margaret McNett Burruss

The phrase “art as prayer” came to me last week during a conversation with fellow artists in an online artists community to which I belong. At the time of the call, I had not been in my studio much for a few weeks. I was heartbroken about the state of the world, and felt rather despondent. But that day I made it down the steps to the studio and did some work that, in the grand scheme of things, seemed insignificant.

It can be easy in times such as these to feel like art doesn’t matter. To feel like “What the crap am I doing? The world is falling apart, and I’m here playing with clay. What’s wrong with me? Am I a just a violinist on the Titanic?”

But it is precisely at times such as these that art matters most. One of my favorite quotes about this is from author Toni Morrison. She describes a time in her her life when she felt devastated by the world around her. She found herself “depressed,” unable “to work, to write,” “paralyzed.” A friend called and snapped her out of it with a rebuke. She wove his words into her own, and wrote in conclusion:

“This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”1

This does not mean all art has to be “on the nose.” It doesn’t have to hit us over the head or slap us in the face with a message. I both write and do ceramics. I’ve never been drawn to art that has an explicit message. But that doesn’t mean there is not something powerful contained in even a coffee mug when it is created from a place of profound longing. Often the song that has great hope was written in a time of great despair. You cannot always tell at first glance, or at all, what an artist has infused in their work, but it will move you, even if you don’t know why.

When this phrase “art as prayer” came to me, another artist was speaking about how the act of doing art changes things. I immediately thought of a sculpture I made when my father started to lose his words to dementia. My beautiful father — the lifelong, prolific writer, journalist, poet and punster, who always had the right word, who tasted words like fine wine, and picked words with precision — now stumbled verbally, searching his mind for the words he loved, telling me over and over “it makes me want to cry.”

The Monster from the Sea, watercolor sketch, 2024, Margaret McNett Burruss

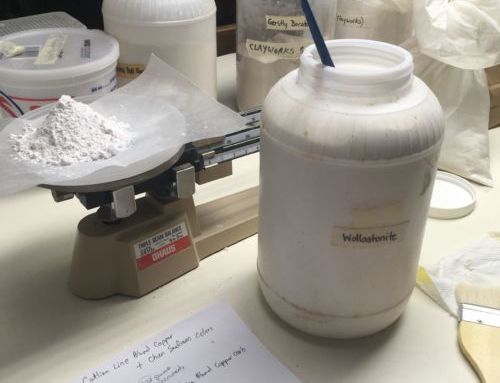

Watching Dad struggle shattered my heart. During that time, I went down in my studio and began making a hand-built sculpture. It started as a tree, but as I was using a technique I hadn’t attempted in over 20 years, it began to morph into a “monstrous heart” with tentacles. Later I cut off the tentacles, and continued to shape the “monstrous heart.” I filled it with holes and etched it with deep grooves. My monstrous heart is still not done. It’s awaiting firing. I had to dry it very slowly and because it is thick. I had to repair cracks that showed up. Now I am testing glazes to decide how I will finish it. It may not make it through the firing and I’m okay with that as well.

This kind of art doesn’t care what anyone thinks. It doesn’t consider time spent a waste of time. It doesn’t care if the final product is “good” in others’ eyes. And while the artist wants to make something “good” in her own eyes, in a sense, whether a particular piece is good is not as important as what happens in the act of creation. The very process of creation changes something. For me, my “monstrous heart” was a prayer for my father, and it was a prayer for my own monstrous heart, which was full of holes and cracking and in need of repair. This kind of art is important, whether it hangs on a museum wall or blows up in a kiln.

But there is something more even than this. The act of creation ignites the imagination. There is a reason why authoritarian regimes criticize, and if they gain enough power, ban, art and books. Art is a fire. When I was a child, I had the honor to be invited to apprentice with the improvisational theater company Living Stage. Later as an adult, I also did a summer workshop with them. The founder Robert “Bob” Alexander had the audacity to believe that art could change the world. He took the theater company into inner city schools and neighborhoods, to old folks homes, to prisons. Bob believed that if a child could imagine in a spontaneous theater production that he got out of bed, walked out his front door, and then blasted to the moon, then he could also imagine a better life for himself.

Imagination is so powerful. It should not surprise us that totalitarians want to stop it. When we surrender to the creative flow, it frees the mind from control. A few months ago, I listened to a podcast from the Holy Post YouTube Channel about “Why Do We Believe Conspiracies,” her surprising conclusion: To overcome conspiracy theories, we need to develop a healthy imagination! This seems somewhat counter-intuitive: conspiracy theories seem so fantastical. It would seem those who believe them have too much imagination, but actually when we have imagination, we can imagine other possibilities and better compare likelihoods. We are able to resist propaganda, and speak truth with boldness.

Here’s the thing, fellow artists and dreamers, imagination is a force to be reckoned with. It’s not something you just turn on in one part of your life and it leaves the rest of your life alone. It doesn’t work that way. When you turn it on, you are able to imagine a better world as well. When you dream of a new color to put on the coffee mug you fashioned with your own hands, and then you find the ingredients and create that color, it doesn’t end there. No! Your mind opens to new possibilities — to dreaming of a community of self-sacrificial love, to dream of all your neighbors treated with dignity and kindness, to dream of love. My dear fellow dreamers. Don’t be afraid to dream. Paint your paintings. Make your tea bowls. Write your poetry, essays and novels. The world needs you now more than ever.

Dream, you dreamers.

1Toni Morrison, “No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear” published in The Nation, March 23, 2015. Accessed February 21, 2025.

Leave A Comment